Early Exhibitions, 1908-1912

![]() After a year of exhibiting American and European photographs at 291, Stieglitz and Steichen believed they needed an invigorating influx of new ideas. Steichen, at the time, was living in Paris and had befriended many artists. Acting as Stieglitz’s European agent, he sent over exhibitions of such artists as Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and Auguste Rodin, whose drawing Hell was exhibited at 291 in 1910. Many of these early exhibitions, frequently the first presentations of these artists‘ works in this country, included innovative ways of portraying the human form that often shocked 291’s audience with frank depictions of sensuality and challenges to conventional notions of beauty. Stieglitz’s aim, however, was not to sensationalize, but to instruct artists and the American public about the fundamentals of the new art and to provoke serious discussion.

After a year of exhibiting American and European photographs at 291, Stieglitz and Steichen believed they needed an invigorating influx of new ideas. Steichen, at the time, was living in Paris and had befriended many artists. Acting as Stieglitz’s European agent, he sent over exhibitions of such artists as Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and Auguste Rodin, whose drawing Hell was exhibited at 291 in 1910. Many of these early exhibitions, frequently the first presentations of these artists‘ works in this country, included innovative ways of portraying the human form that often shocked 291’s audience with frank depictions of sensuality and challenges to conventional notions of beauty. Stieglitz’s aim, however, was not to sensationalize, but to instruct artists and the American public about the fundamentals of the new art and to provoke serious discussion.

Responding to the Armory Show, 1913

In 1913, stimulated in part by the groundbreaking exhibitions held at 291 in the previous five years, the Association of American Painters and Sculptors hosted a large exhibition of modern European and American art at the Sixty-Ninth Regiment Armory in New York, including work by some of the most innovative artists of the period, many of whom Stieglitz had exhibited earlier. Before, during, and after the Armory Show, Stieglitz organized a series of tightly focused exhibitions at 291: first, he showed watercolors by the American artist John Marin, then his own photographs, followed by the work of the French modernist Francis Picabia. Each exhibition included studies of New York City, and thus over the course of three months visitors to 291 were able to contrast how European and American artists responded to the city. In what he called a „diabolical test,“ Stieglitz timed the exhibition of his photographs to coincide with the Armory Show to see if his own art withstood comparison to the latest developments of modern painting.

New Experiments, 1914-1917

![]() In the wake of the Armory Show several other New York galleries began to exhibit modern European art. Unwilling to be one among many, Stieglitz altered 291’s course and, aided by Steichen and the Mexican caricaturist Marius de Zayas, began to exhibit more experimental art, such as that of Constantin Brancusi in 1914. Later that year, with the help of de Zayas, Stieglitz mounted what he claimed to be the first exhibition anywhere to present African sculpture as fine art rather than ethnography. Inspired by their spiritual and expressive qualities, Stieglitz exhibited sculpture from central and west Africa. In 1915 he installed works by Picasso and Georges Braque together with a reliquary figure from the Kota people of Gabon and a wasp’s nest. In this way, he sought to stimulate debate about the relationships between art and nature, Western and African art, and intellectual and supposedly naïve art.

In the wake of the Armory Show several other New York galleries began to exhibit modern European art. Unwilling to be one among many, Stieglitz altered 291’s course and, aided by Steichen and the Mexican caricaturist Marius de Zayas, began to exhibit more experimental art, such as that of Constantin Brancusi in 1914. Later that year, with the help of de Zayas, Stieglitz mounted what he claimed to be the first exhibition anywhere to present African sculpture as fine art rather than ethnography. Inspired by their spiritual and expressive qualities, Stieglitz exhibited sculpture from central and west Africa. In 1915 he installed works by Picasso and Georges Braque together with a reliquary figure from the Kota people of Gabon and a wasp’s nest. In this way, he sought to stimulate debate about the relationships between art and nature, Western and African art, and intellectual and supposedly naïve art.

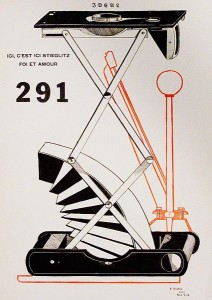

During World War I, 291 became a haven for European artists. To express the new spirit they brought to the gallery, Stieglitz, de Zayas, and Picabia, along with Paul Haviland, a supporter of 291, and Agnes Ernst Meyer, a former critic, launched a new publication named for the gallery. Many articles in 291 applauded America as the most modern nation in the world, but writers also challenged readers to recognize and embrace the central role that the machine played in their life. In 1917 the French dada artist Marcel Duchamp carried this idea a step further when he declared that a machine-made object, a urinal he titled Fountain, was a work of art. Stieglitz concurred with Duchamp, and after Fountain was rejected from another exhibition, he showed it at 291.

Younger American Artists, 1916-1917

Although modern art received greater attention after the Armory Show, few New York galleries showed American works. Deeply committed to American artists, Stieglitz made them the focus of his activities after 1915. In 1916 and 1917 he presented a series of exhibitions of the painters Marsden Hartley and Georgia O’Keeffe, and the photographer Paul Strand, that summarized the dramatic changes that had occurred in American art in the past decade. Each artist had integrated the latest developments in modern European art with their own experience and constructed a powerful new vocabulary of form and color. Despite these innovative exhibitions, Stieglitz was forced to close 291 in June 1917. For more than twelve years he had supported the gallery with his own or his first wife’s personal income, yet mounting financial difficulties, caused in large part by the United States‘ entry into World War I, made it impossible for him to continue to do so.